Shawn Bodden PhD Researcher at Edinburgh University (shawn.bodden@fulbrightmail.org) and Jen Ross is Senior Lecturer in Digital Education and Centre co-director (Digital Cultures) at Edinburgh University (jen.ross@ed.ac.uk)

This blog post relates to the Global Discourse article Shawn Bodden & Jen Ross: Speculating with glitches: keeping the future

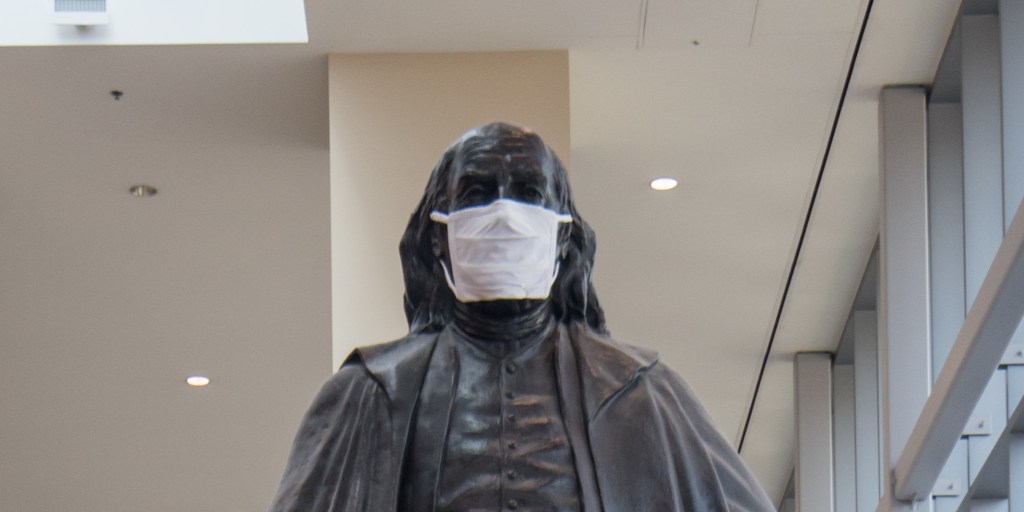

It’s been a year of glitches, large and small. The glitch has become inescapable in the wake of the worldwide disruptions, failures and uncertainties caused by the Covid-19 pandemic and the faltering, inadequate responses of too many world leaders to its challenge in their pre-emptive drive to return to a ‘new normal’. But what is a glitch, and should we understand it as more than an error (technical or otherwise)?

Glitches are a kind of encounter, where expectations, preferences and plans are disrupted, but which thereby provoke new, previously unthought possible futures. By responding to and using glitches, we engage in future-making practices that negotiate what feels possible here-and-now. Irksome glitchy moments can lead us—grudgingly at times—to improvise creative alternatives to our original plans. Rather than seeing the resolution of a glitch as a return to a pre-existing, smooth-functioning way of doing things, speculative decision-making and experimentation involves achieving something following the uncertain situation of a glitch. Repair thus becomes a situated and practical act of reflection on how to work with a glitch: a ‘new’ normal accompanied by lessons-learned, scars, corrosion, raised insurance rates and other unexpected changes. The glitch becomes a space for practical and critical speculative thought about here-and-now possible worlds.

Continue reading